YouTube Diaries, 6 of 6

For the past few weeks, I’ve been using my experiences as a new YouTube creator to write about intellectual property and copyright management. Everything I’ve learned about YouTube and copyright has come from making my videos available for YouTube’s display-ads and then dealing with the various copyright claims and revenue-sharing agreements that come my way as a result. In this final installment, I want to share how a recent video I uploaded was deemed “not advertiser-friendly,” especially in the context of YouTube’s recent squeamishness around issues they deem too controversial so they can appease advertisers.

A few weeks ago, I mentioned the song “Nỗi Lòng Người Đi” by Anh Bằng and how Vietnam’s copyright office had apparently tried to smear his name by attributing it to someone else and saying that he had stolen it. My cover of that song is at the center of this story.

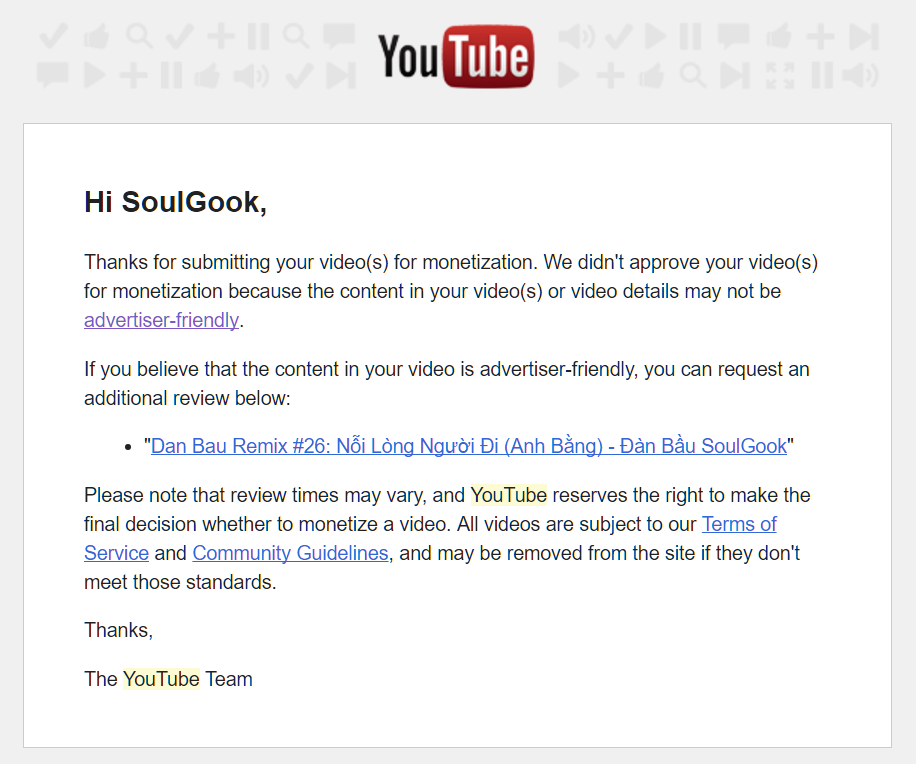

A few days after uploading it I received this message from YouTube, stating that my video would no longer be monetized (i.e. YouTube would no longer show ads on it) because it was not “advertiser-friendly”:

At first, I thought maybe it was because it was banned in Vietnam. As previously noted, Anh Băng’s music has often been banned in Vietnam along with a lot of other war-time South Vietnamese songs. But this song was different…the government had brought it back into its copyright regime, and even concocted some story about how someone else, not Anh Bằng, had written it.

But, if the music was so threatening, why not ban it altogether rather than weave some transparent and strange tale to claim it for yourself?

Indeed, the song is probably not as objectionable to the government as Anh Bằng himself is. It’s not, strictly speaking about the war, but rather depicts the heartache of a man leaving the North when Vietnam splits in 1954. He leaves behind his two loves, the capital of Hà Nội and the sixteen year old girl in his heart. As the song progresses, the girl and the city become metaphors for one another, so that the song is as much a love letter to Hà Nội as it is to the girl. So there’s no real reason to ban the song — it’s about how great Hà Nội is!

In fact, respected singers from Vietnam like Trần Thu Hà have performed it without repercussion.

In other words, this was neither a copyright issue nor a legal entanglement with any entities in Vietnam. What had just happened was all purely due to YouTube’s own abundance of caution.

Just to be clear, YouTube left my video up, but they refused to monetize it because it was not “advertiser-friendly.” I had heard about the stricter “advertiser-friendliness” guidelines, which were a response to the fact that advertisers were pulling out because their ads were showing in videos with hate speech. But what was so unfriendly about my video? Today, there are plenty of versions of “Nỗi Lòng Người Đi” on YouTube, some playing ads, so what did I do wrong?

YouTube’s advertiser-friendliness policy has five restrictions:

- Sexually suggestive content, including partial nudity and sexual humor

- Violence, including display of serious injury and events related to violent extremism

- Inappropriate language, including harassment, profanity and vulgar language

- Promotion of drugs and regulated substances, including selling, use and abuse of such items

- Controversial or sensitive subjects and events, including subjects related to war, political conflicts, natural disasters and tragedies, even if graphic imagery is not shown

Only the last one was even tangentially applicable: “Controversial or sensitive subjects and events, including subjects related to war, political conflicts, natural disasters and tragedies, even if graphic imagery is not shown.”

However, reading my video as controversial or sensitive required making some interesting judgment calls.

First, it’s important to know that I released this video on April 30th, 2017, the 42nd anniversary of the day that Saigon (the South Vietnamese capital) fell and the war ended in 1975. This release date set the stage for a broader context relating it to the Vietnam War. In my video’s description section, I shared how my family members were refugees twice-over, first having left the North at the start of the war, and then leaving Vietnam entirely at its end (read the entire text underneath the video). If YouTube was insisting that my video was not advertiser-friendly (as compared to other versions of this song), then ironically it was because of a connection that I had created myself through the meta-data!

On the other hand, my video was a purely instrumental version, so it had no lyrical content. My description made only oblique references to the war, focusing on my family’s experiences as refugees and immigrants. Yet something about that was not okay.

Has YouTube or its algorithms come to the conclusion that any mention of the Fall of Saigon or April 30th is too political for advertisers? How does that square with the fact that advertisers like Pepsi and Heineken are increasingly making politically-themed advertisements (misguided though they may be)? Is my mention of a meaningful moment in the lives of countless Vietnamese diasporic immigrants really so objectionable when compared to Kendall Jenner co-opting the aesthetics of Black Lives Matter to sell soda or a beer company hawking booze by making a transexual woman sit through some dude tell her that she’s icky?

What in YouTube’s algorithms convinces them that a music video made to articulate a nuanced perspective on the Vietnam War is less “advertiser-friendly” than anything else that’s allowed to show ads? Again, I couldn’t care less about the revenue made from the ads themselves; what concerns me is that there is a judgment call being made by YouTube and it settles on actively excluding discussion of the effects of the Vietnam War on Vietnamese Americans from normal, “ad-friendly” discourse. If my video has now been labeled “not advertiser-friendly,” isn’t it likely that the system has also marked it in other ways? After all, what’s the point of showing a video in “related searches” or ranking it well in searches if it isn’t capable of making money for YouTube? It’s hard to believe that this categorization has happened in a vacuum and YouTube will not otherwise penalize me.

In light of the massive advertiser pull-out recently, I understand the impulse and profit-motive to control the content, but the reliance on algorithms that, in this case, are basically looking for good and bad keywords is an inelegant solution that only serves to marginalize crucial voices. As the Vietnamese American offspring of immigrants, I’ve been told my entire life that we ought to let bygones be bygones and leave the war behind…but if that is indeed true, then why has a simple acknowledgment of my family’s precious history been marked as “unfriendly” to anyone at all?

Examples like this remind us that the recognition algorithms that YouTube uses to manage all the content on its site are not value-free; rather, the mystique of algorithmic processing simply obscures the value judgments that are baked into the whole enterprise. In this case, the judgment is that the very telling of my personal narratives are threatening and controversial, but not in a way they can figure out how to profit from.

This concludes The YouTube Diaries. Thank you so much for reading along and sharing your thoughts. Keep commenting and please let me know what you think I should write about next!