The past few weeks in the YouTube Diaries series have mostly featured something that happened to me on YouTube and my analysis of it relative to issues of copyright and intellectual property. This week, while we’re on the same topic, I won’t be discussing difficulties that I’ve had, exactly, but rather on some broad quandaries concerning cover songs on YouTube. First, I consider how copyright policies are applied when dealing with versions of a particular musical work that reference one another, i.e. cover songs of cover songs. Secondly, I ask, as a practical matter, what exactly are we supposed to do when YouTube has differing policies for different versions of a song?

From France to Latin America to Vietnam to the Viet Diaspora to my Đàn Bầu to Your Screen

The very first song I did in my SoulGook channel restart and rebranding was for Tết, Vietnamese New Year. I picked one of the most popular Tết tunes, “Cánh Bướm Vườn Xuân” (literally, “Butterfly Wings in the Spring Garden”), which was itself based on the melody from the French pop song “Cerisiers Roses et Pommiers Blancs” (music by Louiguy, Spanish-Italian-French dude), famously performed by André Claveau in 1950.

There is something rather palimpsestuous about this situation. First, you have a 1950s French pop song that was eventually re-recorded with new Vietnamese lyrics in Vietnam in the early 1970s. On top of that, it’s likely that the song became popular in South Vietnam not only because of the original French version, but also through Latin big band leader Perez Prado’s instrumental recording in 1955, which had become an international hit in its own right. In 1957, a Vietnamese songbook for “Le Cerisier Rose et le Pommier Blanc” [sic] was released by publishing house Hoa Thủy Tiên with Vietnamese lyrics attributed to a “Huyền Vân,” a pseudonym now attributed to songwriter Từ Vũ but often incorrectly attached to Phạm Duy, who had provided Vietnamese lyrics for numerous other French songs.

Interestingly, neither notation nor Vietnamese lyrics were provided for the song’s minor-key third section from the original André Claveau recording, which was also left out of the Perez Prado recording (and replaced with a peppier-sounding addition). As continues to be the norm for Vietnamese versions of non-Vietnamese music, the attribution in the songbook simply states “Nhạc Ngoại Quốc” (foreign music). For reference, I’ve cued up the differing sections in the Claveau and Prado recordings below:

The earliest Vietnamese recording of which I am aware is one by Carol Kim in 1972 on “Dạ Vũ Mùa Xuân” (Dance Concerts in the Spring), the 26th recording in the Phạm Mạnh Cường series (named after its producer). Carol Kim’s version is a musical model for most recent Vietnamese covers. It features instrumental interludes for both the minor-key section in Claveau’s recording and the major-key bridging section from Prado’s. Overall, it leans towards Latin big band rather than French orchestral style.

This preference for a Latin cha-cha-esque style is seen in recent notable versions, such as Nguyễn Hồng Nhung’s performance in ASIA Productions’ DVD 60, “Xuân thanh bình, Xuân chinh chiến, Xuân tha hương” (Spring of Peace, Spring of War, Spring Abroad). (The embed below is another performance, but it uses the same backing track.)

“Cánh Bướm Vườn Xuân” is inextricably linked in Vietnamese peoples’ minds to springtime and Tết. So even though my version from 2016 was purely an instrumental, meaning it could technically represent either “Cerisiers Roses” or “Cánh Bướm”, its timing evoked latter instead of the former. Additionally, I followed the lead from Carol Kim’s recording to represent both the major- and minor-key third sections of the song, but I also took a few cues from the ASIA Productions recording (particularly its Latin-inspired bass line). However, I also leaned into the minor-key section section from the Claveau recording, playing the string parts almost note-for-note. In Carol Kim’s recording, this section features a trumpet solo that is much simplified in comparison.

With all my explicit references to specific features of multiple versions of this song, I expected to have claims coming from many different sources, but this is what I got instead:

It’s a tad annoying that they don’t even name the claimants, making it doubly difficult for me to take actions except through YouTube’s built-in arbitration system, and it makes it impossible to follow the chain of rights without at least seeing what parties are involved. Do versions of “Cánh Bướm Vườn Xuân” already pay royalties to the creators of “Cerisiers Roses”? When my ad revenue is split, does all of it go to the Vietnamese rights holders for “Cánh Bướm” who in turn manages the “Cerisiers Roses” rights, or are the “Cerisiers Roses” rights-holders already included in the claimants that I can’t identify? Or, is this part of the copyright chain just not accounted for at all, and my ad revenue never actually makes it back to any version of “Cerisiers Roses,” be it Claveau’s, Prado’s, or anyone else’s?

Every Vietnamese version of this song is already a cover of a cover, since they all use musical cues from both the Claveau and Prado recordings, but is that something Content ID can handle? Note that the point in the song that has no claim is between 1:20 and 2:20 — that’s where I pretty faithfully adapted the minor-key section from Claveau’s recording. The fact that it’s gone unrecognized either points to (1) a flaw in the algorithm’s ability to parse out these little palimpsestuous markers or (2) my lack of skill in playing the song in a way that resembled the original enough to be recognized.

Spring Gardens and Purple Rain

What I’ve featured here is an interesting story of song covers spanning the globe and the difficulties of figuring out the rights for them, which I think would be true regardless of whether YouTube’s Content ID algorithms were doing the “figuring out” or not. These are the sorts of connections that require historical and cultural context to understand, and I’m not sure these new-fangled digital brains are quite up to that task yet. But what about song covers that are created from within the intellectual property system itself, where the connections are clearly documented and agreed upon by all the stakeholders, and they’ve done so fairly recently? Surely nothing can go wrong in these situations!

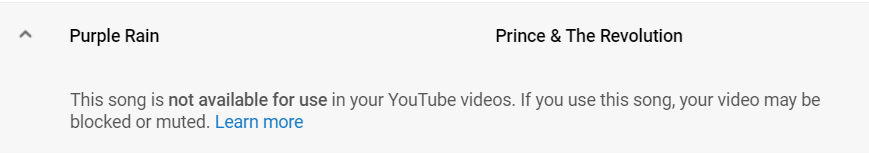

Of course they can. My final illustration for this section is more hypothetical, but there’s also a bit of necessary context: after Prince, our beloved “Purple One,” passed away last year, I was really eager to do a tribute to him. I had all kinds of ideas for covers of “Purple Rain,” “When Doves Cry,” etc. However, Prince was famously careful about his copyrights and particularly afraid of internet-based streaming services, so he jealously guarded his songs on YouTube, Pandora, etc. Even today, after the record labels worked out a number of deals with his estate (Pandora can stream Prince again, for example) this is the YouTube Music Policy for “Purple Rain”:

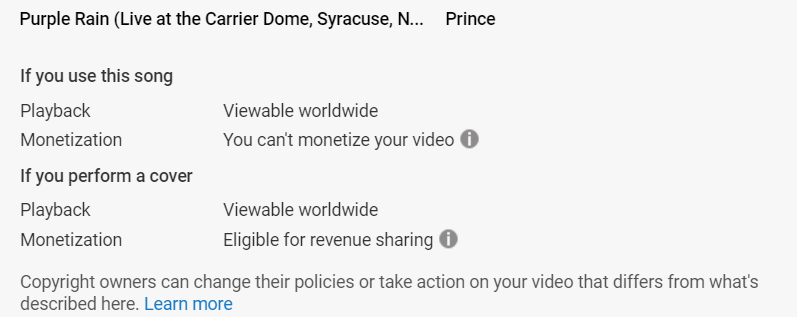

So, it’s a shame that I’m barred from doing a cover song, but that’s understandable, and at least it’s clear. But just above that entry is this one:

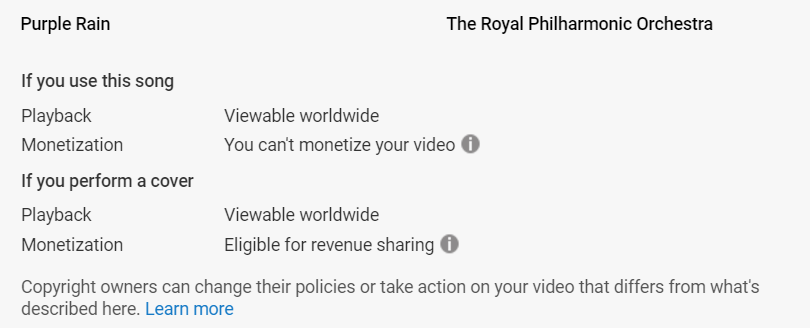

Wait. This clearly says that I can do a cover of his live performance of Purple Rain at the Carrier Dome, with the normal monetization agreements you normally see. But how does one do a version of Purple Rain that is a cover of his live performance but NOT of his original recording with The Revolution? And it gets even wilder:

Based on YouTube’s Music Policy, I can do a cover of the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra’s cover of Prince’s Purple Rain, but I CANNOT do a cover of his original recording. So how would I distinguish between the two…just add timpanis?

The mechanical reason for these discrepancies is pretty obvious. A bunch of different rights holders just uploaded into the Content ID database generalized guidelines for their entire libraries of content, which occasionally overlap with one another, but nobody has bothered to iron out the discrepancies. Nonetheless, I’m still not certain what this means for me if I want to actually make a cover of “Purple Rain.” I’d like to just give it a try and see what happens, but I’m afraid of getting a strike against my channel. On the other hand, there are some pretty cool covers already up, so maybe it’s fine:

Intellectual property laws work on rather simplistic models of cultural transmission and thus can’t handle the fact that human beings take inspiration from just about anything they can get their hands on. This is compounded by algorithmically-maintained copyright management systems that only allow for limited, largely unidirectional ways of acknowledging the relationships between musical artifacts. Until I either figure out what the actual policies are or just stop giving a damn, it looks like the world will be deprived of a đàn bầu cover of The Purple One.

Thanks to everyone for reading! Please comment below or share your experiences or thoughts about cover songs and intellectual property on YouTube or in the world in general. And do come back next week for the final entry in The YouTube Diaries, when I’ll discuss a recent video that was marked as “not advertiser-friendly.”